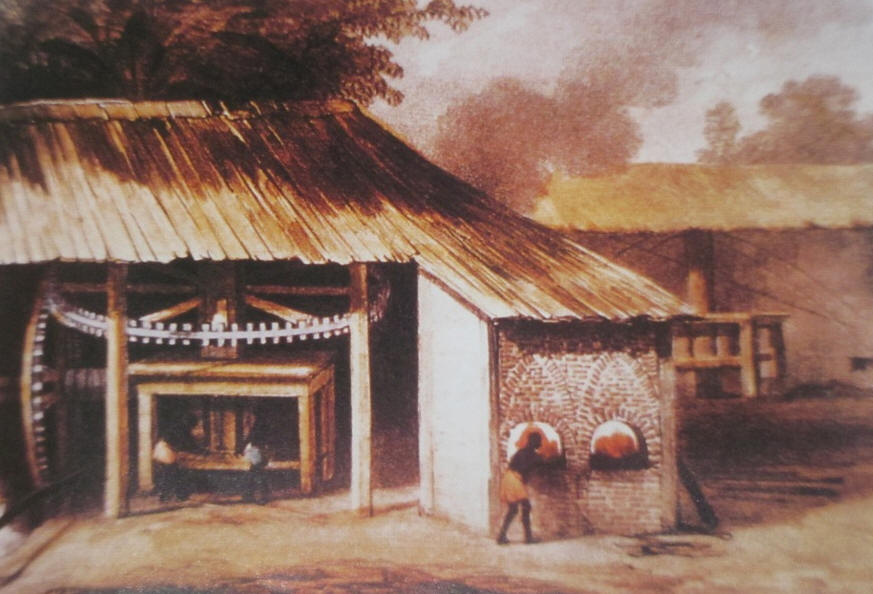

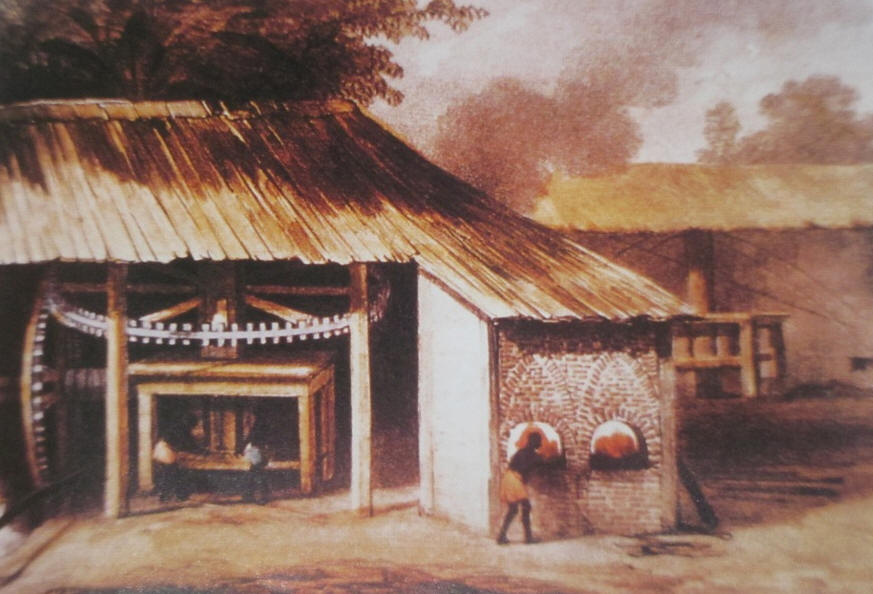

This image of a 1839 watercolor by Pierre Jacques Benoit 1782-1854 is of a water-powered sugarcane crusher in Surinam; he painted many scenes in Surinam during his 1839 trip.

The Portuguese introduced sugar to Madeira and Sao Thomé in the 1530s (ref 106), but according to Jonathan Israel (ref 8), it was the advent of Brazilian sugar after 1560 that stimulated the formation of a large Portuguese conversos maritime trading community, and its relationship with the Sephardic diaspora. Portuguese conversos in Brazil and Portugal linked with Sephardic Jews in Venice and Pisa, but then Amsterdam, Hamburg and Livorno, in importing Brazilian sugar to Italy and northern Europe. This pattern broadened, so that twin diasporas of conversos and Sephardic Jews interacted and grew in symbiosis with the national trading networks of Spain, Portugal, Holland, France, England and Denmark. After the fall of Pernambuco in 1654, the Dutch trading axis of Curacao and Amsterdam developed; and it is observed (ref 40) that Dutch West India Company records show that almost every top-ranked Curacao Jewish merchant had a close male relative in Amsterdam. This trading axis before long was rivalled by that of Barbados and London; the English in 1660 with the new Navigation Act barred Dutch ships from the English trade as a reflection of the desire of the English to benefit from its West Indies colonies - in competition with the Dutch - at the expense of the Spanish. The Spanish and Portuguese trade with their colonies suffered through their harsh treatment of their conversos and Jews who emigrated to more hospitable places, or retreated to isolated locales where smuggling did much damage.

Barbados was the oldest of the English colonies, having been settled in about 1627, and almost from that year Sephardic Jews began to make their homes there. The Barbados model of sugar cane production and processing was based on that developed in Dutch Brazil and brought from Pernambuco by Sephardic Jews. Barbados sugar pioneer James Drax visited Recife around 1640 (ref 129). Barbados sugar production boomed in 1646-50. Dutch merchants played an important role with advice and finance. The first Synagogue was built in 1654. So relatively numerous were the Sephardim and so prosperous did many of them become that at one time there were 2 independent Sephardic communities in an island the size of the Isle of Wight. The origin of the Barbados Sephardim was in many cases the same as those of England and there was a close 2-way relationship – the young ones coming to seek their fortunes and the older ones returning to seek other business opportunities or to retire. Thus some of the best known names at Bevis Marks (Barrow/Baruch Lousada, Henriques, Massiah, Abudiente/Gideon, Navarro, Bueno de Mesquita) were familiar on the island. Samuel (ref 5) details some of the other pathways by which the Barbados Sephardim came before 1680. There were opportunities for advancement - as merchants or by land acquisition from bankrupt estates as indebtedness was always significant. Barbados sugar exports rose from 75 tons in the early 1650s to 190 tons a decade later, with an additional 30 tons from the Leeward Islands and 10 from Jamaica. An evocative picture of the life of a planter in Barbados emerges from ref 92.

The Barbados Lousadas had a historic connection with sugar technology - from ref 5 we learn that Gracia Lousada, sister of the magnate Aaron Lousada of Barbados, was the wife of David Mercado who came from Pernambuco and who developed a new sugar milling technology which attracted attention and support.

The expulsion of Jews from Pernambuco had many consequences other than the spread of sugar technology to Barbados and Surinam. Ref 49 conveys the dramatic story of the voyage made by expelled Pernambuco Jews to New Amsterdam in 1654 - these 23 were the first Sephardic Jews in North America. Fairly quickly thereafter, at Newport RI, they developed into active Atlantic traders, exporting rum they made from Jamaican sugar, to Africa and elsewhere.

|

|

|

This image of a 1839 watercolor by Pierre Jacques Benoit 1782-1854 is of a water-powered sugarcane crusher in Surinam; he painted many scenes in Surinam during his 1839 trip. |

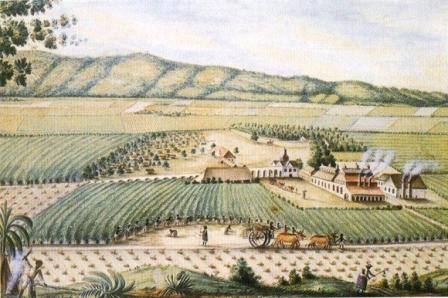

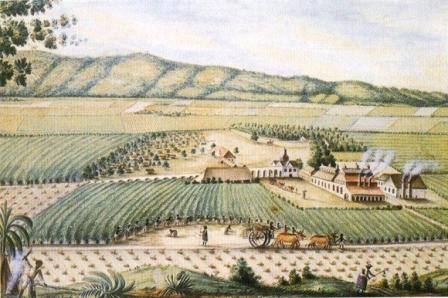

Watercolor c1800 of the Richmond sugar estate, Jamaica, by John Henry Schroeter who was a plantation surveyor but he also served as captain at Fort Balcarres, Jamaica. His military training was evident in the maps and plans he produced of various estates; in fact he was amongst the first, prior to 1800, to show the variation of the true magnetic north. Many of his plans had attractive vignettes or cartouches added. His watercolor paintings are done with the same quality and accuracy. This view shows the workers in foreground, loading an ox-cart, and with good detail to the mill and plantation buildings with many slave huts to left. The basis of the early sugar estate was to design the plantation in a circular fashion so that no great distance was to be travelled from the huts to the fields and return to the mill. |

Jamaica became progressively more attractive as a

sugar-producer; it had a great reserve of virgin lands and the Barbados soils

and timber (for boiler fuel) became somewhat depleted.

In the mid-1660s, the governor of

The Lousadas, as can be seen from the wills, owned Banks and Carlisle Estates in Jamaica, but also through their financing of other growers from time to time owned other estates like Richmond above.